Architectural Digest

Meghan O’Neill

From a design perspective, cities are in a unique position when it comes to climate change. Among the largest sources of emissions globally, they are also highly vulnerable to its consequences. According to one report, 70% of cities worldwide are already dealing with the effects of climate change, and nearly all cities face some kind of risk. But they are also potentially powerful agents of change. Policy at the national level has moved painfully slow in most countries, but urban areas have the authority to make meaningful changes in land use and zoning, transportation, green space, and energy policy.

Large cities like New York and Tokyo are working toward ambitious environmental master plans, but smaller cities also have a role to play. In Denmark, places like Copenhagen are successfully harnessing variable wind power, part of an effort to become the first carbon-neutral city by 2025. Now, the Danish Energy Agency is exporting that know-how to China, and when such solutions are scaled up to a national or global level, impact can be immense.

Building cities from the ground up, as many in China are, should present an opportunity to create greener, healthier built environments. But retrofitting existing infrastructure, coastlines, neighborhoods, and buildings, and creating adaptation plans is also paramount, though more difficult. Fewer than half of European cities have climate adaptation plans in place; worldwide, only 18% of cities with populations of more than 1 million do.

Others, however, are taking increased resiliency seriously. Boston’s pioneering master plan by SCAPE to adapt and transform 47 miles of shoreline, for example, will increase access to open space and protect the city during major flooding events. To combat flooding risks in Bilboa, Spain, city planners opened the Deusto Canal, making the Zorrotzaurre peninsula into an island. The canal and its vegetated banks now allow the river to flow through, reducing water level by a full meter.

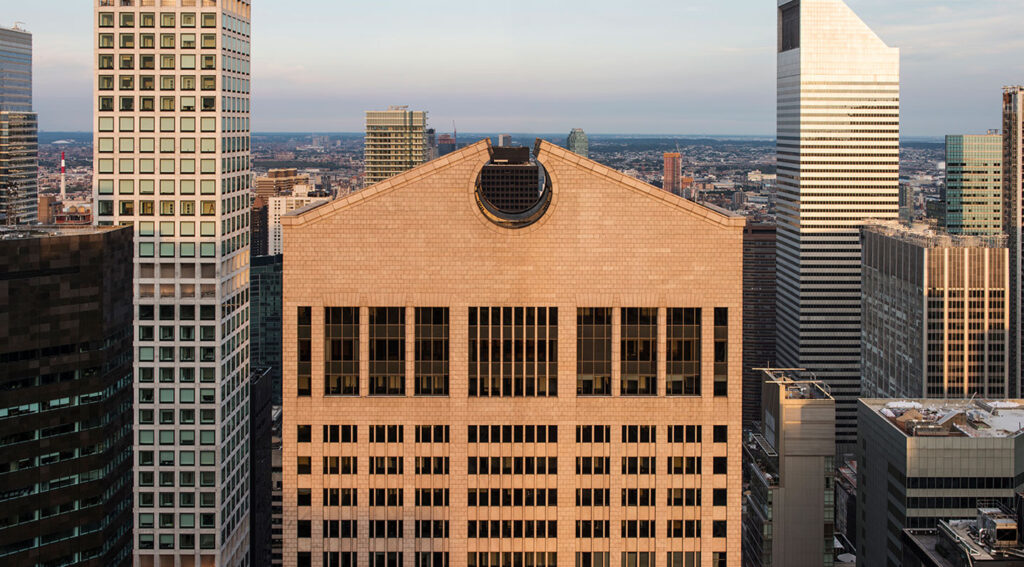

Such projects aren’t always large-scale, or even funded by the public sector. At 550 Madison in New York, originally designed by Philip Johnson in 1984, a retrofit will meet LEED Platinum standards and deliver access to the neighborhood’s largest public green space. Nearly double its original size, 550 Madison’s stunning new garden and water feature, redesigned by Snøhetta, is an asset not only to building tenants and occupants, but to the public too.

“Privately owned public spaces have always been important in New York City,” says Michelle Delk, partner and landscape architecture discipline director at Snøhetta. That idea is “elevated right now as people are more concerned about climate change.” And as research shows that access to nature can improve mental and physical health and productivity, well-being is becoming a central topic in the transition to greener cities.

How people move through cities also matters enormously to emissions and human heath and happiness. Neighborhood density, ease of multimodal transit, space for varying nonvehicular traffic, and pollution must all be considered. That means finding new ways to use our existing car-driven infrastructure and prioritizing micromobility, safety, walkable neighborhoods, and last-mile delivery—not just automated vehicles.

Those principles drive the design of Toyota Woven City, a 175-acre experiment at the foothills of Mount Fuji, designed in collaboration with BIG. Powered by hydrogen fuel-cell, geothermal, and solar energy, the plan envisions a refreshing and logical equity among types of mobility, people, and nature.

Roads are split up for three purposes, with designated areas for faster motor vehicles; a recreational promenade dedicated to micromobility, such as bicycles, scooters and other modes of personal transport; and a linear park for pedestrians, flora, and fauna. Roads weave around three-by-three city blocks that are organized around a courtyard. The result is a safe, outdoor space accessible only to pedestrians, surrounded by buildings that are still easily serviceable.

BIG’s designers began by imagining ideal historical cities before the introduction of automobiles. “Our main takeaway was that when you need less room for cars, parking, and idling, you get more space for people and nature,” says Leon Rost, partner in charge of the project, which begins its first phase next year. As more modes of personal electric transport emerge, BIG’s design for Toyota could have far-reaching effects on how existing cities approach transit infrastructure and, in turn, reduce emissions. “Cities have proven again and again that they can change their modes of mobility,” points out Rost. “It’s really a question of retrofitting the streets.”

For companies like Uber, however, economic and environmental sustainability means operating within the existing infrastructure—where the individual car is the primary mode of transport—but rethinking how it can be used more efficiently, says Emily Strand, head of public policy for Uber Movement, a division of the company that shares anonymized insights about traffic and mobility. “We know we can’t just make the roads bigger,” which would lead to more cars and congestion, she says.

That’s one reason the company is looking at multimodal transit as part of its corporate approach; it has already added Jump e-bike shares, supports better bike infrastructure, and recently rolled out an app that can help commuters sync up various legs (e-bike to train to Uber, say) of a route. “The vision is to be able to streamline that experience seamlessly,” says Strand.

That bridge between the technological and physical city is also critical to progress. More technological innovations—buildings or vehicles that monitor and relay air quality or congestion in real time, say—can help make everything from transit to energy use more efficient, and pleasant. But collecting and sharing this data is crucial; transparency is a must if greener cities are to emerge.

Uber Movement, for example, can provide anonymized data sets about how and when traffic is moving through a particular city or neighborhood. Analyzing these trends over time can help policymakers alleviate gridlock or assess how congestion pricing might work, says Strand. At the University of California Berkeley, data scientists used travel times to create a tool for the Bay Area that works like a Waze for fuel efficiency.

Getting people out of individual cars and into ride hails won’t move the needle on emissions, but it can help us move away from the idea of a car-centric streetscape by discouraging car ownership and reducing the need for parking. The age of design for individual automobiles is over, says Strand: “Cities of the future are going to be built for people.”

To combat climate risks, urban planning must increasingly be driven by human health and well-being and technology that can support vibrant—and verdant—urban settings. “It’s tempting to think about the city of the future as very Blade Runner and sci-fi,” says BIG’s Rost, “but it was a turning point in our project when we realized what really mattered was open space, clean air, and connection with other people.”