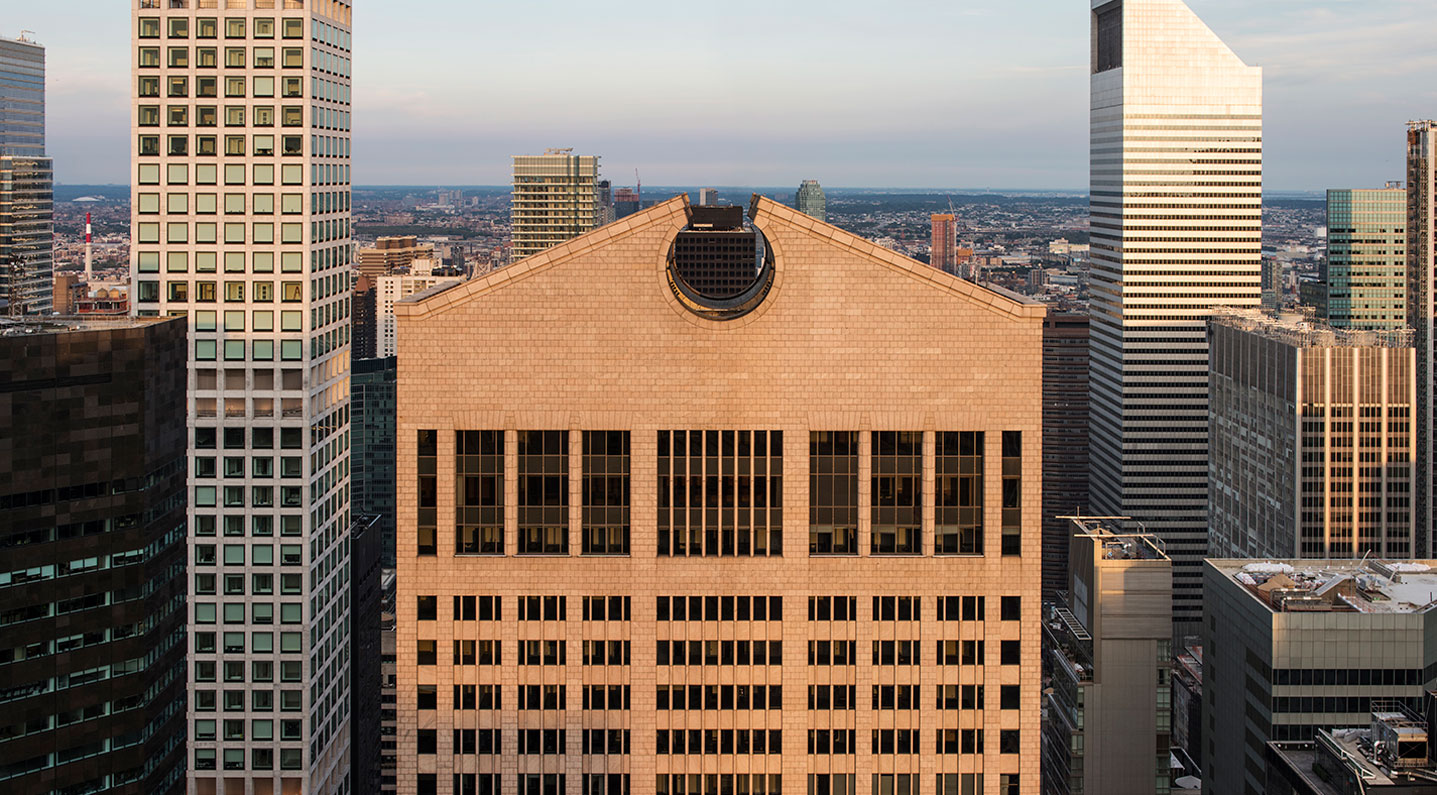

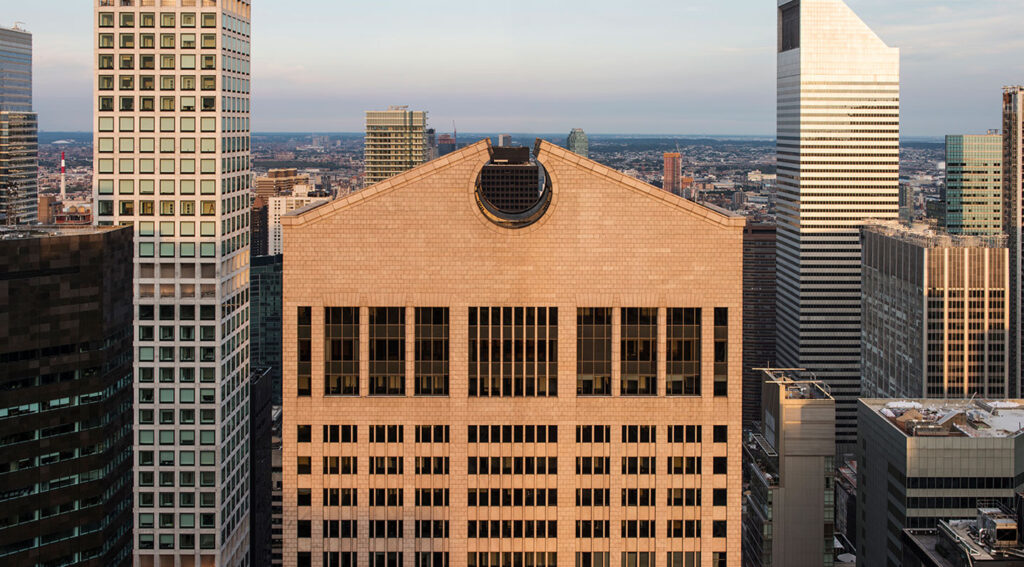

Philip Johnson, with his partner John Burgee, cooked up what’s now called 550 Madison for AT&T. The weighty granite facade, the towering, pulled-taffy proportions and supersized Italianate portico were all meant to project AT&T’s heft and permanence. Then the building opened in the midst of the telephone company’s breakup.

People don’t realize hiding inside that Chippendale exterior is a remarkable structure by Leslie Robertson, our greatest living structural engineer, who was the engineer of the Twin Towers. He’s creative in a way comparable to Eiffel. As you know, Gustave Eiffel’s structure for the Statue of Liberty suspends Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s copper sculpture from a central spine, much like the construction of a sailboat. Robertson does something similar here. Basically the way the AT&T Building works is that there is a spine going up the building that is the core, stiffened with steel plate and diagonal bracing to parry the majority of the forces due to the wind. In addition to that, there is a horizontal truss at the top of the building, and that ties the central spine to the columns of the building.

In essence, the building is like a sailboat, where you have a mast up the center, and then you have outriggers tied by cables to the hull of the boat, so when the wind blows, the outriggers and stays stiffen the mast. It’s an incredibly efficient and elegant way of stabilizing the building.

Invisible from the outside. I play the piano and I know how certain things, which an audience may not focus on, are meaningful to pianists, because they know what went into them.

To me Robertson is a virtuoso.

Read the full article on The New York Times website